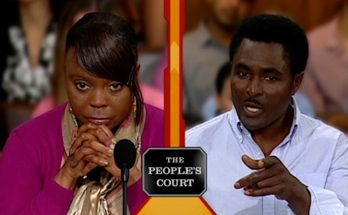

In a case that captured the attention of many, Lisette Freyo sued Olivier Rabbath, a self-proclaimed artist and shoemaker, for $648, including $590 for a pair of custom-made shoes and additional shipping costs. The dispute arose after Freyo, who ordered a unique pair of shoes from Rabbath at a craft fair, experienced multiple delays, sizing errors, and failed attempts to have the shoes fit.

After several rounds of communication, with no resolution, Freyo decided to take the matter to court, seeking a refund and reimbursement for her efforts.

The story began in February when Freyo ordered the custom shoes for $590, after having her foot measurements taken by Rabbath. The deal seemed simple enough: the shoes were promised to be delivered within 8 to 12 weeks.

However, the delivery was far from prompt, with Freyo receiving the first pair only after 15 weeks, well beyond the agreed timeframe. To make matters worse, the first pair was too small for her to even wear, and Rabbath later explained that he had mistakenly sent the wrong pair intended for another customer in Los Angeles.

Despite the initial mistake, Freyo remained patient, returning the first pair and waiting for the second pair. Another 4 weeks passed before she received the second pair, but once again, the shoes were too large, rendering them unwearable.

At this point, Freyo decided to send a friend to personally deliver the second pair back to Rabbath, demanding either a full refund or a third attempt at creating the right size. Rabbath agreed to try again and promised to deliver the third pair in a few weeks.

When the third pair arrived, Freyo was again disappointed. The shoes were too tight, making them impossible to wear. By this time, Freyo had lost faith in Rabbath’s ability to fulfill the contract, prompting her to seek legal action.

She filed a lawsuit claiming that not only had Rabbath failed to meet the terms of the contract, but his repeated errors had cost her extra time, effort, and money.

Rabbath, a shoemaker who prides himself on being an artist and not a traditional shoe store, defended his actions in court. He argued that Freyo was an extremely difficult customer, consistently complaining and criticizing his work.

He also pointed out that Freyo had not personally come in for fittings after the second attempt and had sent a friend to do so instead, which he argued was a key issue in ensuring the proper fit. Rabbath, who teaches shoemaking and has been supported by the Smithsonian Institution, contended that the shoes he made were “one-of-a-kind” and emphasized that he had done his best to please Freyo by trying to accommodate her via phone conversations and attempting a third pair.

Despite Rabbath’s argument that the fit couldn’t be accurately corrected without Freyo’s direct involvement, Judge Marilyn Milian took a more balanced approach. She acknowledged that while Freyo’s decision to send a friend instead of attending the fitting herself may not have been ideal, the fault ultimately lay with Rabbath for agreeing to make adjustments over the phone and failing to ensure a proper fitting in the first place.

Milian made it clear that, as an artist in business, Rabbath was still bound by the same contractual obligations as any other professional or business. She also noted that his delay of more than 20 weeks was far beyond what was promised.

The judge also highlighted that despite Freyo’s somewhat unconventional approach by sending a friend, it was Rabbath’s responsibility to ensure that his work met the required standards and fit properly. The fact that the artist had made repeated mistakes and failed to resolve the issues in a timely manner, compounded by the fact that Freyo had to pay additional shipping costs for each of the returns, left her with little recourse but to seek legal action.

In her final ruling, Judge Milian ruled in favor of Freyo, stating that Rabbath had not upheld his end of the contract. She ordered Rabbath to pay Freyo a total of $648, which included the $590 for the shoes and $58 in shipping fees she had to pay due to his mistakes.

The judge also decreed that the three pairs of shoes, which had been returned to Rabbath, should remain his property.

Milian’s ruling emphasized the importance of fulfilling contractual agreements, even when dealing with artistic endeavors. In this case, the shoemaker’s pride in his craft did not exempt him from delivering what was promised within the agreed-upon terms.

The case also shed light on the responsibilities of artisans and independent contractors in meeting customer expectations, especially when they are running a business and taking payments for their services.

This legal battle serves as a reminder to both artists and customers that clear communication, adherence to deadlines, and ensuring that contracts are fulfilled are essential for a successful transaction. It also underlined the crucial role that patience and persistence can play in seeking justice when expectations aren’t met.

In the end, Lisette Freyo’s decision to take the matter to court not only resulted in a refund but also set a precedent for how similar cases might be handled in the future.

The case concluded with a lesson for both parties: for Freyo, the importance of managing expectations and handling grievances directly with service providers; for Rabbath, the realization that his artistic freedom did not absolve him from the business obligations that come with accepting customer orders.

This courtroom drama, with its emotional twists and turns, left a lasting impression on those who followed it, showing that justice can be served, even when it involves handcrafted shoes.